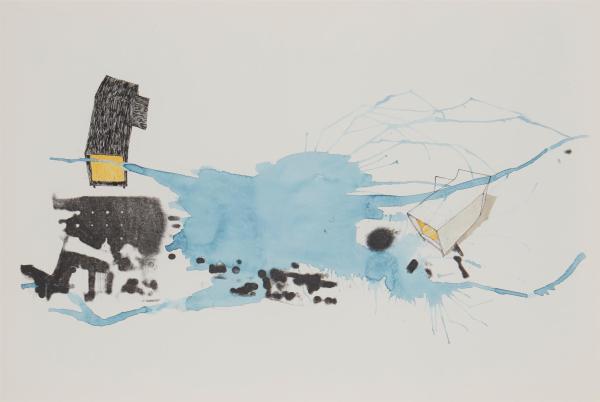

Recently auctioned, a work from the series Untitled (loss/entry/return) #00005, 2005, Xerox [solvent] transfer, ink and graphite on watercolor paper; and an exhibition at Frederic Snitzer Gallery.

Loss/ Entry/ Return offers works based on a journey of perception. Drawings, photos, sculpture and sound are the tangible manifestations of moments along the way. What we experience is the process of voyaging from indeterminacy to clarity, from vastness to specific identity. Ideas of guidance and presence are constant throughout the works.

From an email sent to the gallery for the press release.

With “loss/entry/return” Guerrier shifts ground. You see the artist looking through binoculars at the expanse of the metropolis. But it’s not a real city. This is more like a superimposition of events, black blotches and green tempera splashes (with directional tentacles) moving near the background of the metropolis’s silhouette. Amid these images you find linear sentence fragments, silent remarks as if coming from a lost century of ideologies.

Then one discovers this conspicuous cantilevered solid structure — a sort of corbel — that the artist draws in most of his pieces. I read a bit into it: In architecture, cantilevers separate themselves from the ground; they are singular, impulsive. What’s more important, they don’t subjugate the territory.

Guerrier is slowly moving away from the dense existential “feel” of reality expressed in his earlier photos. He has become a more gregarious, unconventional observer, exploring his own situation in relation to the rest of us. Now he should incorporate into his photography some of the new elements present in this series.

At the exhibit, an important local curator helped me see a bit of French theorist and filmmaker Guy Debord in Guerrier’s work. Suddenly the seemingly disconnected one-liners inside the drawings made more sense.

In his 1967 Society of the Spectacle,Debord warned that our lives had become transactional relationships. Spectacle was a key concept for Debord, who borrowed from Marx’s idea of alienation. We become alienated from ourselves when everything we do, we do for the sake of abundance. The spectacle then becomes the sad and endless race to own more, which, paradoxically, turns into an abundance of dispossession. Some of this message is already present in Guerrier’s promising cityscapes.

Alfredo Triff, City Views and Latin News, Miami New Times, April 21, 2005.